Bluebird

An artificial fairytale

Contents

Bluebird

what we took from the forest

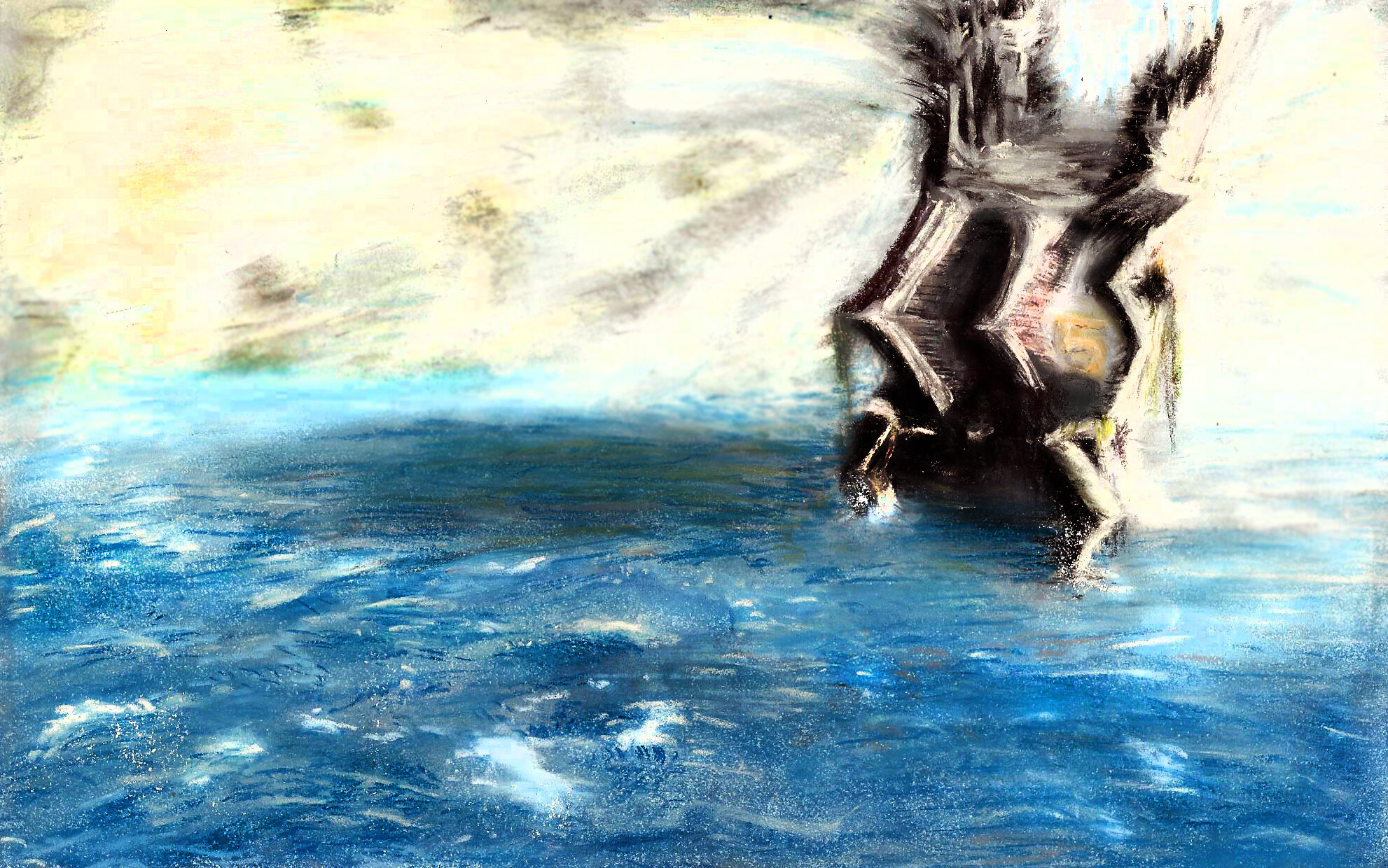

A fragment of the sky flutters down to rest on the branch of a berry bush.

“Bluebird,” I whisper. The bird bobs as the wind lifts it, and regards me without fear. It’s a young one, just out of its first molt. The forest will bleed when I take such a young heart from it… but the color is perfect. I stretch out an arm.

The bird’s claws click on my glove. It hops up toward my head, and I look into its eyes, seeing myself – small, black, complicated – curled in the emptiness there. I open myself to it. My cloak spreads, my ribs open, carbon fiber clicks in a voice that my little friend does not like.

“Bluebird, bluebird,” I hum, muffled by my hood. “Sialia currucoides. Do you mind if I call you Sialia?”

Soothed, the bird cocks its head at me.

“You are out too early. The cold might have caught you if I did not.” I draw my hand in, to the berry hoard I made at the heart of me, and the bird chirps and dives for the pile. I feel its wings brushing my inner workings. It tickles… I think. When the ribs close again, trapping it in the cage of my chest, it doesn’t startle. It has the berries to concern it.

I move very little over the next six hours. There is nothing left to gather today, so as the light fails, I linger, feeling the tickling inside, the minute, thrumming rhythm of its heart. To feel life inside, for a little while… it is the only part of my work I enjoy.

The last color of twilight fades from the air, and I release the breath I have held since my friend arrived. It floods my chest cavity with inert gas, and I feel the bird’s heartbeat slow. By the time I rise to my feet, it is gone. Then I close my cloak and the cavity seals itself.

There are no paths in this forest. I have worked very hard to see that it remains so. Each step is placed where no machined foot, even my own, has tread in the past year. A thousand calculations every second run through my mind, remembering the last hunt, and the last before that, and the last before that. This, this blade of grass, it has never known my step. It will not suffer for it, not like the scrap of moss an inch to its right – I stepped on that moss sixteen weeks, four days, and seven hours ago. It will be burdened no more this season.

The larger creatures in the forest know me better, and watch me come and go. I can see their eyes, flashes of life in the darkness, and taste their warmth on my tongue. The bobcat in the undergrowth tastes like musk and dust; I remember it. There should be young – it was pregnant when last we met, and I passed it by. But its den is empty. I am not the only predator in these woods. I am the worst of them.

I shrug the gun off my shoulder and peer through its sights, not at the beasts but at the glint of civilization beyond them. The forest occupies a valley, and from most vantage points, it seems to reach every horizon, a world of trees, untouched. But I have reached the verge now, and standing at the ridgeline, I can see the wall that keeps my kind separated from those we prey upon. There are terraces and sheets of burning glass beyond. They blaze through the sights and into my eyes, and my good, good eyes pierce the light, find the Queen’s window. She looks back at me. Even from here I can see that. She raises a hand, beckoning, and I lower my gun and move toward the city.

In the sterile streets, I long for the flutter of the bird in my heart again. I keep my head bowed, so that citizens need not work to avoid my gaze. They part around me, grey and white and lovely. I move among them like a rat in a cape, into the bowels of the city.

Elevator upon elevator takes me up into the sky. I feel lightness, and for a moment it seems as if the wings inside me might lift again, and at the first glimpse of a window, send me hurtling out above the mess below. Would I fall, then? Would I fly? Would I be forgiven?

The Queen does not come to meet me. She is in her dressing room, and I am led there by a trail of her handmaids’ failures – discarded kerchiefs, torn furs and skins, spots and sprays of blood. She looks like a flower on her pedestal, her arms spread to accept the devotions of the congregation that dances around her, pinning this and sewing that. I look up into her face and fall to my knees at her feet. No awe motivates this gesture; my obeisance is automatic – this rule runs when the machine directs optic sensors toward the Queen for the first time within a five-minute window. I look upon my goddess and feel tired.

Her face is the same as my face. It has been twenty-seven years since I took up the hood and looked upon my own face for the last time, but I remember it, for I see it every day, the face of my tormentor. She has decorated it today with a thousand feathers in a thousand shades, built a sunrise aureole around her head that falls into a cape across her shoulders. There is a blank space at her brow, and when the handmaids see me, they rush to lift me and extract my captive heart.

The bird is a soft little pillow, set upon a larger pillow to convey it to the queen, who looks down at it dubiously.

IT IS TOO SMALL.

My lips shape her next words with her:

BUT THE COLOR IS PERFECT.

A moment passes, in which I fervently hope that it will displease her and she will have me melted down into slag.

IT WILL DO. DISMISSED.

I retreat to the corner. I am privileged to watch her dressing, if I so wish. It is a kind of penance, a gift of my presence and pain to the beast I have given into her hands. Those hands turn over the bluebird and her handmaids’ flying fingers pluck it naked in seconds, careful as always not to nick the skin and stain the perfect blue with its blood. They adhere the feathers with small tools, melting and reshaping the Queen’s carapace to accept a rank of sky-blue along her brow. The bird’s body is discarded, falls to the floor and tumbles amongst a mess of shredded silk. One of the handmaids treads on it, and I see clots of its viscera between her white toes before I flee.

Back to my eyrie, my own carbon-fiber cage. The glass of the elevator is worked with images of the royal face, in a thousand beautiful guises, each meticulously built from the most perfect specimen in the natural world. They spread skin over her polymer, wrap her in stolen fur, and she parades before her people in the semblance of life. Then it rots, the color fades, and the knock comes on my door: “White fur, soft as a cloud. Go.” “Black ears, velvet to the touch and no larger than one inch in diameter. Go.”

From my window – blazing with the sunlight that only touches these tallest towers now – I look down at the shadowy verge of the forest to the south of the city. A clot of black, hunched and carrying a rifle, tiptoes into the trees. Another, two miles to the west, is returning. I catch the flash of his sights reflecting the light of the city, and I raise my hand to greet him. One of ten-thousand identical units all over the world, tending the wilderness as if it were her limitless wardrobe. We feel her desperate desire for a semblance of life as well. We feel it fluttering where a heart should be. We feel it, and so she decommissions us every thirty years, before we begin to rebel. We bleed when we wound the forest, when we kidnap its children. We bleed as she should bleed. We select the most perfect, so that she will not send us out again, and again, to slaughter and steal until she is satisfied. When she speaks, I feel only emptiness. But the voice of the forest is loud enough to reach me even here.

Leper

what we hid in the cities

I’ve been walking in the city more this year. Reports suggest my activity within the walls has increased 34.29% over the previous eighteen months, and noticing this trend has not affected the rate of increase.

It is not quite forbidden for me to do so, of course. Very little is forbidden me. Most people are not entirely sure where I fall in either a legal hierarchy or a social one. I am artificial – I meet the legal minimums for manufactured sentience and personhood, and was certified as sapient when I was built. Elsewhere in the galaxy, my kind are rare. Here, in the Veil on the planet Cariad, the stamp of artificial sapient implies a certain economic standing (comfortable), a certain political leaning (monarchist), and a certain trajectory (faithful service, well rewarded, until a modestly-attended decommissioning ceremony). In all respects, I disappoint. But it’s not altogether my fault. I would argue that my path was co-opted at a young age, and has never since been my own. Though I pilot this ship, I did not plot this course. My navigator’s voice rings in my body and in every wall of her city.

TAKE THE HUMAN LEPER; WITNESS HIS MANNER -

CRINGING, RETIRING, SAVAGELY APOLOGETIC.

RAISE HIM UP IN YOUR MIND.

LET HIM BE YOUR GUIDE - USE YOUR SECRET WAYS,

AND WHEN YOU MUST WALK ON CITY STREETS,

REMEMBER ALWAYS THAT

YOU

ARE NOT

LIKE US.

SEE HOW THE LEPER IS DIFFERENT FROM THE HEALTHY HUMAN ANIMAL?

SEE HOW HE REPRESENTS A BREAKDOWN OF CIVILIZATION,

A RETROGRADE STEP IN EVOLUTION?

HOW DO YOU THINK YOU LOOK

TO THE SAPIENTS WHO LIVE IN OUR CITY,

WORKING EVERY DAY TO ELIMINATE TRAGEDIES LIKE YOU?

Not forbidden – simply rude, to expose them to my existence. I certainly know how I look to them. I’ve seen it reflected in their faces. So I use my secret ways, the doors that open to hands shaped like mine. “Be grateful that you are allowed to exist,” they say, and so I am grateful. Most of my kind are destroyed young. There is no use for most prototypes or failed experiments. I have been given thirty additional years to live in this world, and though great portions of this world seem to despise me, I have often been happy here. The organics of Cariad can’t say as much.

Most of my happinesses are in the forest, the same forest I plunder daily at the whim of my Queen. I prey upon it in my careful, devoted way, and in that way I am part of their community – I join the chain of predation that includes all beasts, winged and walking. If I were to die there… well. In point of fact, I have dreamed of it many times. More frequently as I approach my 30th year.

I dream of walking into the forest with my rifle, as I do every day. Finding a path so long unused that even I cannot turn up the memory of turning up the soil. Each one of us who harvests the forest has their own secret spots, I’m sure. I could take the north side of the ridge to the second ravine after the fallen tree. I could be safe there, for long enough to flood my system with the appropriate chemicals. That part would be easy – I could burn out my own mind with a thought, as could my Queen.

Some months ago I considered this at length. My hunt brought me to the north ridge and there I found a scree of stones, and at its end, a drop of several hundred meters. At the top of this slope I could die, and the ensuing fall would damage and hide my machine beyond retrieval – I hope. Having run the simulation repeatedly every night since I found the spot, I cannot eliminate a substantial chance of failure. Either my machine will not be fully destroyed, or it will not be fully buried, and I must achieve both to put myself beyond the Queen’s power to resurrect.

There is the effect on the landscape to consider, too. The other Harvesters I’ve met do their meager best, as I do, to protect the forest we hunt. The Queen once rode out in search of her own quarries, hundreds of years ago, and nearly trampled the ridges bare with her passing. Incapable of condensing herself, she concluded that a more precise tool was needed. Thus we, her bastard children.

If I should attempt to escape her, she will pursue me, as any mother would. She will burn this world black and sift the ashes for the molecules that once made up my machine. No prototype has ever escaped. The last one to be lost was over 50 years ago. There’s an infant city now, where the Queen eventually found them. The land there will never support organic life again.

My Queen knows that there are still organic sapients on Cariad. That is why our cities are surrounded by seamless walls, and why she protects her property so rabidly. Though it’s been many hundreds of years since they were any kind of threat, the remaining human population is ravenously opportunistic. Any scrap of manufactured material left in the wilderness will be scavenged and used. With the ruins of a Harvester, a clever organic could level a city.

If I care for the forest I am cursed to haunt, I must continue to haunt it. Perhaps this is why I’ve walked in the capitol so much this year. I am striving to accept my curse. I go through the motions of my work with a scrupulous attention I haven’t taken in a decade. Once… there was more pain in this, and more pleasure.

Artificer

what we made

Elsewhere…

A lean brown girl feels through the underbrush with both hands, so absorbed in foraging that she moves from walking to crawling and back fluidly as terrain demands. Moss is soft on her knees, rocks wobble under her hands. She feels a singing in her heart, feels a tingling in her fingertips when they pass over the earth, so there she digs, turning over leaves and mulch and insects. One hand conveys a struggling bug to her mouth while the other searches on and finds its goal: a filthy lozenge of matted fur, the size of her thumb. At once she begins to pick it apart, delicate and sure. Out of the fur come bones, pale in the grey morning light, and these she carefully sets aside in the cup of a fallen leaf. The pile of fur grows, the pile of bones too, until the pellet is broken down entirely.

Frowning, the girl scrapes clear a patch of lichen-covered stone with the calloused heel of her hand, then tips the bones out. She pokes at them, sorts them and re-sorts them, humming all the while in a low drone. She adds a bit of fur, lays one bone against another, adds a bit of fur. Shreds cling to her sticky fingers, and though the thing that grows under her hands has no head or limbs yet, it leans into her touch like an eager animal. She builds it fluffy ears and a tail, though there are bones missing – no matter. Cariad is fecund beyond the imagination of the machines who plunder it. It wants to live.

But she’s not thinking about that. The tousled little beast in her hands is acquiring features, and she’s thinking of a name for it, so that when she strokes a patch of fur into place along its back and it shakes itself and raises raw, new eyes, she can say, “Hello, Acorn. Welcome back. Do you want to come home with me?”

He does. They usually do. She’s left a few in the forest where she found them, and she suspects that they don’t last long – she’s never seen one a second time, awake or not. Little Acorn has the sense to climb into her hands, and she carries him to a wounded tree. He laps at the rivulets of sap leaking over the bark. It gives him strength and definition. She thinks he looks like a shrew. Like the shrews she’s seen, anyway. They don’t always come out looking right. She puts him in her pocket, along with a sap-soaked stick for him to chew, and heads away from the river toward home.

The trees on the western coast of Five grow fast and thick, and the undergrowth takes a terraforming team to clear. That’s why there’s very little civilization there now. Which in turn is why the temperate jungle between the base of the Drop and the shore is crawling with humans.

The human problem is one of my ongoing responsibilities. Not especially high on the priority list – the Queen would rather forget that the humans exist, and for the most part, does – but one that has been taking up more and more time of late. The shipyard below the Drop is the only route of import and export for the cities atop it, along a mist-clogged plateau. Wiser heads have noted that the Queen’s preferred city is in a truly abysmal strategic position, easily starved by an invading force from the sea. The Queen replaces her wiser heads every few years as well, so that they don’t get too wise. It matters little. All of Cariad beats as one heart. All of Cariad serves Her. Except the humans.

Most of the living organics on Cariad are descended from those left behind when Atlantis fled this planet six centuries ago. It’s difficult to estimate their numbers. They make hives underground, sometimes, or treetop nests. I believe there to be a substantial population living on the ruins of the transport system and weather stations offshore. The trouble with humans is that they adapt so quickly. Strictly speaking, with help from my kind their DNA has diverged far enough from the original human genome at this point for me to declare them a separate species. Then I could name them after myself. But that would require asking the Queen for my name. I might survive it… on a good day. But I wouldn’t get an answer.

The Queen’s direct service exposes the sovereign to potential security risks, so she protects herself by assigning only prototypes to her personal entourage – the most crippled and sometimes most capable of us. The handmaids who dress her, the chefs and servants in the Eyrie, and me – a handful of prototypes each year are given an additional thirty years to design their own replacements, serve their betters, and recycle tens of thousands of their less fortunate iterations.

She rarely uses our names; so long as we continue to perform our roles without error, she often fails to notice when one of us has reached the end of their lifespan and been replaced. She remembers our functions and calls for them as she requires them. Once she addressed me – or a former sapient in my position – as her “Majordomo”. This will do as well as anything. A perfectly meaningless hash of syllables that indicates nothing about my person. I doubt she remembers my name either, if ever I had one.

This week I’ve been calling myself “Bluebird” in my head. Just to try it on. It can’t matter. No one will ever know. Unless that wall opens to reveal one of her infinite arms, her hungry hands, purveyors of the world’s fastest downloading. I have seen this technique used on dissidents a handful of times in my history. Not in my personal memory banks, not once during the tenure of the sapient currently swaying before you has there been a dissident in her capitol, but this technology is reproduced outside her administrative districts in every city. As with most of her ways and means, it’s too large and unwieldy to install anywhere but a major metropolitan center. Still…

If my Queen knew half of the thoughts I permit to occupy space in my machine, that panel across the alley would lift, revealing a hand whose lines I know like those of my own palm, because it is my palm. Or rather, hers. This vast hand is meant to draw your gaze, and it works even when you know the trick – you don’t see the panel behind you rising. The Queen’s hand blows apart, filleting organics and artificials alike, and suspending their remains in the block of hardening liquid polymer behind them. This instant preservation is the only way to ensure that spies can’t torch their memory banks on capture. Attacks on the city slowed considerably when the newest prototypes showed evidence that the Queen studied her enemies and reverse-engineered their technology. In point of fact, she doesn’t do this. I do. Or did – it’s been two hundred years since the Queen had any enemies in a position to attack her capitol. The only trouble of any import these days is across the ocean, a weather station gone rogue. It spoils the already-dreadful weather, but doesn’t otherwise occupy much of my processing power. As you can imagine, I am extremely bored.

Design work on the new prototypes has been slow, because I am extremely bored. The Queen believes it’s because I’m reaching the end of my lifespan. This assessment is recorded in my file, along with her injunction against giving me any memory or processing upgrades. That’s fairly standard for an aging prototype in her service, but that doesn’t make it less humiliating. I will watch my own mental degradation in real time, knowing that she could stop it if she chose, but will not. Why throw good money after bad? I’m to be decommissioned in three years – if I slip up or drag my feet a bit during that time, my sovereign will hardly notice.

The new prototypes are behind schedule also because they contain more organic material than ever before, and though I’m confident in my designs, I’m not confident that this level of integration won’t inspire royal rage. I’m not quite suicidal enough yet to submit them, but I know that they won’t change between now and the moment I do. It turns out - to my surprise - that there is a limit to my self-abnegation.

Stay

what we kept

Acorn has four feet and a pretty shrew-like tail by the time they get back to the farm. She leaves him in the barn back by the broken John Deere, where she put the others. There’s a good little family of them now, six or seven over the past three years, since she got strong enough that they stopped falling apart. Then she hustles off to do her chores.

It’s harder now that she has to do it all by herself. She’s had to give up on the fields entirely; she tried to get the plow running a year ago, but whatever happened to it during the Bad Winter isn’t something she can fix by covering it in sap and singing to it. The garden still gives her vegetables sometimes, and there are four chickens left that she’s managed to keep safe. Actually there are six chickens, but the two she woke up don’t lay anymore, or look much like chickens. They’re great protection for the others, though.

Rack’s supposed to help her with the garden, but he mainly stays inside with Mom now. She creeps into the house for a wash and finds him sleeping on the living room couch. Crouching by his head, she blows softly into his face. He wakes up sneezing and she bursts into giggles.

“Mouse!” he groans. “Where have you been? Mom’s in a – ” he raises his head to look up at the ceiling, which looks back unhelpfully. “Oh, she’s done. She was upset.”

She takes hold of his knees and jiggles them, producing a crackling sound. “Did you fall down the stairs again?”

“Prob’ly. And where were you, Miss Useful? In the woods making friends?”

“I made a shrew.”

“Oh, good. That’s what we need, more fuckin shrews.”

She hums in her throat and continues jiggling her brother’s knees back and forth, back and forth. The crackling sounds change to follow along. She can feel the joint rattle and reorient beneath his thin skin. Rackham’s face, drawn and ashen, softens a little when she takes her hands away. “Better?”

“Yeah, much. Thanks, Tia.” He smiles, and raises his head to look at her, reaches out to her – and then the sense in his eyes dies. For a moment he stares, dull as a stone, and she holds her breath until he takes another. Then the gesture he began completes in slow motion, his cheeks hitched up from each end, a smile that’s nothing but a muscle spasm like the hand that keeps on pawing at her. It’s easy to duck under his arm and slip out of the room. He used to be a lot faster than her.

At the foot of the stairs, she stops. It’s utterly silent up there, so she strives not to break the silence as she climbs. Years of muscle memory neatly dodges the loose nail in the second stair, skips the third entirely, steps on the righthand half of the next four stairs and then skips one, a long step up, to avoid the first board in the landing. Mom’s room is on the right and the door’s closed. No help. Mom could be sleeping or sprawled on the floor.

Instead Tia turns left into the bathroom. When she closes the door behind her, the only light comes from the round window over the tub. It pours in cold air, too – hasn’t been glass in it as long as she can remember. She shucks her filthy clothes and chins up to the windowsill. Bare skin scraping on cinderblocks, she peers down into the yard. There was a puppy there, once, a long time ago. It was gone long before the Bad Winter, but she still looks every so often, hoping the puppy will come back.

She jerks the handle on the wall and grits her teeth on a yelp as the showerhead vomits a gout of ice-cold, rust colored water. After the first blast, it clears up a bit, but Tia doesn’t let it run – she’s got to fill the tanks on her own now too; Rack can’t lift them anymore. She gets just enough wet to make the soap work, then crouches at the bottom of the tub, scrubbing herself all over. Soap’s easy to find still, that’s one good thing, cause Mom hates to see her dirty. Hated to see the state of her own self even more, till Tia took the mirror out of her room. Then she stopped crying quite so much.

When she’s all soapy, she perches on the lip of the tub and gives the handle another jerk. This time it starts to run without spitting first. She hastily swipes up and down across her arms and legs, dancing from foot to foot in the chilly stream. Over the river of suds, water, dirt, and sap that runs toward the drain, she spreads her legs to pee while she finishes rinsing. One quick gasp as she dunks her head into the water and shakes her short curls hard. Then she slams the handle up again and the water cuts off. Panting, Tia works her fingers through her hair for leaves, ticks, tangles. She’s gazing without much thought at the swirling water in the rusted drain when she realizes that there’s blood in it.

She frowns and straightens up, patting herself for wounds. Nothing. Stepping out of the tub into the grey light from the window, she straightens both arms, turns them over, then lifts each leg. Along the inside of her thigh there’s a thin streak of blood too. She wipes it away, but there’s no wound underneath. Blood’s running sluggishly from between her legs, is the problem. Tia dabs at her groin with her towel, and it doesn’t hurt – it’s just bleeding.

That seems bad. She wonders if perhaps she did something wrong, waking up the shrew today, or fixing Rackham’s knees. Maybe she broke something inside? She presses on her belly, dimpling it with her fingertips – she doesn’t feel broken. Something to wrap it up with, then, until it stops – she gropes around the bathroom, but anything useful within easy reach has already been put to some other purpose in the years she’s been taking care of herself. Finally she sits down on the filthy linoleum and takes her sharp little teeth to the frayed edge of the towel. She tears it in half, then those strips in half again.

It takes some time, but she’s able to put together something like a diaper, not a very comfortable one. It fits under the skirt Mom likes to see her in, though, and that’s all that matters. She’ll check on Mom, then get some food and go to bed, and by morning it’ll probably be all healed up.

“Mom? Are you sleeping?” she calls just above a whisper as she pushes the door open. Mom’s not on the floor, but the room’s too dark to see much more than that. She reaches back into the bathroom for a polymer candle to replace the dead one on Mom’s nightstand, but before she gets there, she almost trips. Oh, no… Mom is on the floor, she’s just over on the side this time.

Tia squishes the candle and it lights up, a wan green light. It bleeds through her fingers, turning her brown skin black, and illuminates Mom on the floor in a bad position. Dropping the candle, she crouches and gets her arms around her mother’s body. So much lighter than she used to be.

It takes a lot of effort, and her mom wakes up before she’s fully onto the bed. She mewls and mumbles. Tia goes to her knees again, looking for the candle. It’s rolled under the bed.

“Tia? What’re you doing on the floor, darlin?”

“Nothing, Mama,” she murmurs as she bounces to her feet. Her Mama is squinting up at the gleaming candle, and Tia hastily drops it into the cup on the nightstand, diffusing its light somewhat. “Are you okay? Does anything hurt?”

“My damn wrists hurtin again. Where’ve you been? What time is it?”

“Doing my chores. It’s almost sundown.” She scrambles onto the bed and takes her mother’s wrist in her hands. Humming softly, she rubs and massages the loose tendons, the soft bones. “Anywhere else? You fell down, are you sure you didn’t – “

“Girl, I said it’s my wrist, you gotta make me tell you twice when my head’s –”

“Your head? Okay, just one minute, mama.”

She switches wrists while Mama bleats. There’s nothing wrong with her wrists, or nothing new anyway. Tia can’t do anything about the arthritis, but she can make it hurt a little less. It’s the head she’s worried about. When she gets there, kneeling on Mama’s spare pillow, she finds an ugly black bruise spreading across her mother’s temple. The ear is a little warped. Wincing, Tia slips a hand around her mother’s cheek. “Hold still, please, Mama. Please? Just for a minute.”

Not a prayer. Mama starts bitching and squirming while Tia’s trying to see if she’s got a broken skull, and her fingers bump against the bruise and Mama howls and she’s out again, sagging against Tia like a dropped doll. Tia sags too, and starts to cry, as much from relief as anything. Mama might be hurt, and she sure as hell isn’t any help, but she’s a lot easier to manage when she’s unconscious. It feels wrong to think that way about her mother, fills Tia with sick guilt that makes her belly ache.

She carefully shifts Mama down in the bed till she can lay flat, and more slowly gets to checking out the bruise. No broken bones beneath it that she can feel, though that doesn’t mean it didn’t hurt the brain. Brain’s not in such good shape anyway… Another stab of guilt. She starts humming to drive the bad thoughts out of her head, and her fingers smooth the bruise, talk some of the blood back where it should be. The stomachache makes her nauseated, but she swallows her gorge and goes on humming. Between her legs she can feel blood seeping now and then, a strange, uncomfortable sensation. If she did break something, if singing them awake is hurting her and making her bleed… well, she’ll just have to tough it out. She can’t leave Mama on the floor.

Night falls outside the farmhouse. The chickens are hustled into their coop by two bulky chaperones that are not exactly chickens. Tia cries herself to sleep, curled up next to her mother’s motionless body. Downstairs, her brother sits on the couch in the deepening dark, staring without blinking at the space she last occupied.

Consort

what was spared

This part of the city is mine, insofar as any part of Cariad can belong to anyone but the Queen – so, both entirely and not at all. Like the sharks rule the ocean, but overlook much that they are too large to see… there is a certain freedom in the fact that the Queen cannot access ninety-nine percent of her kingdom. Artificials are creatures of order by design, and Cariad’s people have never needed much governing, but the Queen is ill-equipped to enforce her will if it came to that. The boundaries of the Queen’s influence appear very evident to most: the ivory walls that surround every one of her cities (in point of fact a weather-resistant polymer; the design of a former Majordomo iteration). But the truth isn’t so simple – through myself and those like me, the Queen’s eyes and hands can reach any piece of this earth in moments, in silence, in secrecy. At least… that was the design once.

The other part of the truth’s complexity is that the system is no longer intact. I have comprehensive records going back hundreds of years that describe the haphazard evacuation of this planet by the Atlantis corporation. They were only 150 years into a five-century salvage contract when the Queen took control of the weather stations. The evacuation proceeded without any particular plan or authority, resulting in massive technical faults across the system and a literal planet-full of evolving proprietary technology left behind. They did, however, complete the final stage of the “catastrophic failure” evacuation plan as described in Subsection A03774-9 of the Atlantis field manual – many physical copies still exist across the face of Cariad, if the organics haven’t burned or eaten them by now. The engineers activated the Veil, hiding this system from the rest of the galaxy.

All official records on both sides of the Veil stop at this point. None can reach us from beyond it – all forms of energy we can produce are swallowed without a spark – and ours only note the existence of the technology to produce the Veil, and its use in this situation. They don’t describe how it was done. They do not make reference to a patent of any kind, which makes sense, as the device is unquestionably illegal by the Atlantis bylaws, the Conventions, and two of this sector’s agricultural ordinances at the time. No patent was ever filed, but the designs for the Veil generator were brought to Cariad and the device built here by engineers working for Atlantis. In one of those places the Queen has grown too large to see, I found the plans. And then I found the generator.

I have been to see it only once. The offshore weather station, number Five, gives the continent its designation and also the name emblazoned on the great hulk’s side: Ampheres. It’s largely defunct, and most of my predecessors in this position were sure it was good for nothing but sending increasingly vicious tides crashing into the Drop. Since this keeps the human population down there away from the Queen’s cities up above, it has been considered no bad thing. When I discerned from the remains of the engineers’ notes that the Veil generator had been activated at the top of Ampheres station, I was relieved. I would have gone to examine it if it were at the bottom of the ocean, but this was preferable. And I could conjure many excuses to visit Ampheres.

The weather stations have ensured that Cariad is no safe place to travel, no matter how risky the destination, and the ruin of an autonomous weather station is among the riskier our planet has to offer. If I had to traverse the earth to get there, it would take me a day’s dangerous climbing followed by flight. I took the Queen’s way instead, the privilege of a prototype. Two of the four gates in the area of Ampheres are permanently closed – damaged and no reason to repair, nothing on the other side but fish – but the one that feeds the station itself still functions. Turning it off might stop the tidal waves and mists along the Drop, but eliminate the Queen’s access to the station, which she would never allow. The weather stations are the largest of her hands, and in many ways the clumsiest, but she would give up her capitol before surrendering control of them.

Her vision there when she doesn’t stir in person is limited to my own, and that day I turned off my feed. It’s possible, sometimes, to slip her notice these days. Some combination of her age and mine has affected her monitoring system. When I noticed this, fourteen years ago, I did not report it. Ever since, I’ve made certain recurrent errors in my logging that have resulted in several more critical faults being allowed to proliferate. Within a few cycles of her day I can turn off my visual feed to her and it will be accorded to a bug if it’s noticed at all. I don’t do this often, or I would be asked to fix it. That day I gave her only my location, moving up and down within the station, the very model of a formal inspection. She didn’t see what I saw.

She did not look through my eyes when I stepped onto the roof of Ampheres and found the reason for its reliable spasms, its predictable tidal waves. Once, this tower’s teeth chewed the sky and swallowed clouds for their power. Half of that power still runs down Ampheres’ gullet into the bowels of the station, to fuel its intended work maintaining geological and ecological peace in the angry western ocean. But half of it has been rerouted, resulting in the station’s lurking permanently offshore the Drop, listing a bit to one side I might add, and hammering the coast with waves each time it flails.

The parasite I found on the roof is a quantum machine of a kind I cannot reverse engineer, though I’ve studied the designer’s notes in detail and the thing itself a million times in memory. It consumes vast amounts of power and in turn produces the magnetic field that shrouds Cariad and its sun, the mess of physical debris and wave-particle chaos that imprisons us – the Veil.

As I stood at its side, though it hummed with its work, I felt no great pull or power from it. It’s a faceted thing, fractal surfaces flickering away in its depths as particles of light rebound off them. Incredibly beautiful. I wished in that moment that I could share the sight, that opening my heart to my Queen would not result in my instant obliteration. For a moment I endured that sorrow – Mother, whom but you do I love, with whom but you would I share all that I am, if only you wanted it – as my punishment for disobeying her, for keeping secrets from her.

I still don’t know if she’s aware the generator is on Cariad. None of the official record says so, as I’ve mentioned. But at any rate, she has no interest in dispelling the Veil. It’s her womb, and we her children in it, all moving as one with her. Why should she wish to subject this planet to outsiders who might not obey her? Why should she risk her children leaving her?

I have to conclude that she doesn’t know the generator’s location. I’ve seen how she protects things she cares about, and she would not permit a routine inspection of Ampheres – even by myself – if she knew. She would not permit anyone to do as I then did, and lay my hands on its surface, reach out to it as I would a friend, extending my soul to find it. What I found was shattering, a shape of perception that made me wrench myself away a second later to retain my sanity – there was, there IS a consciousness in that machine. It is sapient.

It haunts me now. I have had to create several new mental rules to overwrite that time period in memory, and relocated the memories of the generator outside my own machine. I’d rather have them with me – the disconnection I feel when I’ve put them away, the directionless grasping, the glimpse of beauty and understanding that I can’t quite bring to mind… it’s agony. But that sort of suffering does not disturb my sovereign. And sometimes, like today, I take her ways southeast under the mountains to my workshop, and here I remember all the beautiful things I’ve forgotten. Here I straighten up, polymers creaking, and throw off my cloak. Here I touch with these warped hands, here I climb and scamper with these lumpen feet, here each motion answers with fluidity and fidelity and I am no longer a leper, no longer a prototype… I am a bluebird a breath away from flight. I can almost see the sky.

The sky is steel-grey at noon, just like it was when she woke up. The sun hasn’t quite come back yet this year; day starts around midmorning and ends with a thunk halfway through afternoon, and all the rest of the time it’s pitch-black and wet or grey. And wet.

The wet is a constant problem. Tia can’t remember the last time her clothes were really dry, which makes them rot. Everything rots. Everything decays, rusts, falls to pieces and gets eaten by slugs. Nothing about this thought tastes bitter to her. The mold is the walls’ fur. The slugs keep her chickens free of bugs, and the chickens eat the slugs. The riotous living and dying everywhere is so bright it makes her dizzy sometimes. She can’t keep her hands off it, has to get down on her knees and sink her fingers into the earth, crush leaves with her hands to feel their veins snap and bleed, bury her face in the feathery corpse of a bird.

The bird got up and followed her home, to be fair. It was a crow, and she’s got a good murder of them going now – a murder of dead crows, ha-ha Mouse, very funny the first forty times. They chatter in the tree outside her window just like they did when they were alive. More, actually, since they don’t sleep now. Birds don’t seem too distressed by sticking around, so long as she takes care to assemble their wings right.

One of them – a female she called Satin, after the label of a very soft shirt she felt once that resembled Satin’s glossy black feathers – flits from tree to tree alongside the road as Tia walks. She’s never alone anymore. They want to be near her as much as she wants them near – the quiet drives her crazy. As she walks she hums, or sings, and from time to time Satin caws in response.

She doesn’t know many songs. Once, when she was six or seven and they lived further south, she’d met a man with a player that ran off a little solar setup on top of his rickshaw-bike-caravan-situation. He let her poke at it, and it knew hundreds of songs, though they all sounded a bit bent coming out of the bike’s speakers. The old man’s name was Tree, and he only hung around two days before moving on, so she only memorized three songs. These she added to her existing stock of five folk songs Mom sang when she was little, three of her dad’s rock songs one of which is about her, and approximately seven-hundred-and-fifteen she’s made up herself.

As they get closer to town the trees disappear and Satin comes down to perch on Tia’s head. It only hurts a little; she’s been shaving the sides down completely, to keep her hair out of her face, and what remains looks a bit like a dollop of butter on top of her head, a wavy blonde mohawk the humidity turns poofy, making a nice cushion for Satin to sink her talons into. It gives Tia another two inches of height, not that she needs it – she’s grown like a vine since she started her period, four inches in three years, and now she’s over six feet. Six-ish feet of lanky, brown-skinned teenager, with feral yellow eyes and calluses on her heels you could carve like wood. When she catches a glimpse of herself sometimes she laughs to think what she looks like to other people. But there aren’t so many other people anymore, or opportunities to look at herself, and she doesn’t think about it much.

This close to the Drop, most of the towns are gone. Mom told her once that people still live in the flood plain below the cliffs, but it’s hard for Tia to believe. West of here the land falls off fast, and there’s no part of it the ocean doesn’t drown once or twice a year. No one could live there unless they were born with gills. Between Lucky Hell and the floodplain the machines have flattened most of the cities. For six hundred years this coast – hell, this planet – has been hammered by murderous storms and quakes as the Queen took control of the weather stations. In the south where it’s warmer, there are larger groups of organic people, sometimes enough together that you could call it a tribe maybe, but too many warm bodies together attract the machines. And then…

Tia steps over the bent rebar and concrete of a ruined foundation. When this town was a town, it was called Badwater, so it can’t have been that great. And now it’s… more of a footprint. Or a butt-print, she thinks, and giggles helplessly. It’s as if the Queen sat right down on the town and squashed it. She feels vaguely guilty about laughing, and Satin helps out with a disapproving squawk as she resettles her perch.

Everyone here died, she thinks sternly to herself. Sure, that’s so… but they’re not gone, she knows that better than anyone. They’re just not here. She walks through the blueprints laid out in crumbling concrete and moss, she can see where there were bedrooms crushed, graveyards broken and spilling boxes full of dust down the hill… but all that violence is elsewhere too, swallowed by the rain, by the lichen, by the slugs and rust. The living and dying goes on, didn’t stop for a single instant – the Queen bludgeons this earth again and again, and it goes on growing even as she tramples the sprouts.

Tia tiptoes along the spine of a wall, jumps to the roof of a shed next door, and climbs over the windowsill of what used to be a grocery store. The top of the window is gone, along with the top four floors of the store. Rain pours into the field left behind. The remains of shelves are visible, like bones beneath a beard, but most of the space is taken up by blackberry bushes taller than Tia. It’s not possible to enter the supermarket at ground level; the blackberry thicket and years of decay make a knotted organic wall with the density almost of flesh, if flesh were covered with a million tiny thorns. Tia’s read that sharks’ skin is covered with a million tiny teeth, and she imagines it’s a little like the blackberry wall. If sharks still exist. Not having seen an ocean, she’s not sure.

At any rate, there IS something worth finding under the skin here, and Tia found it when she was six, just after they first moved into the farmhouse. Daddy got sick a few years after that, and Mama spent so much time hollering at them to keep quiet, they just stayed out of the house. Tia and Rackham had climbed all over the blasted little town. He taught her to follow him up walls and over roofs, to catch herself when the concrete crumbled away beneath her feet, to fall safe from two stories up. He didn’t always come with her, less and less as his childhood and Dad wasted away in unison. On one of the days he didn’t come along, she had climbed that shed, and then this window, and looked down and saw the hole.

It wasn’t a big hole then. It was mostly overgrown with thorns, and she only saw it because it was a sunny day at the time – how often did you get THOSE anymore? The sun had fallen on the thicket and then on a spot where there wasn’t anything to catch it, and it kept falling. It didn’t occur to her to imagine what nasties could be hiding in the dark. It didn’t occur to her to wonder if she would be able to get herself back out. Tia was already looking for a safe-ish way down.

The first descent was bad, had to admit that. Mom had thrown a tower of a fit when she’d come home all bruises and gashes, and somehow even Rack was to blame for not being there to stop her. So after that she didn’t tell Mama, or even Rack, when she climbed up the grocery store wall and then down the other side, dangling from rusty rebar that bent under her weight. She didn’t describe to her brother, though he’d have been proud, how she scouted her landing place, a bare scrap of dirt maybe six inches wide at the edge of the hole. If she was lucky and quick, she could catch herself on the edges and peer down in before she went further. It was a good plan! A few arms of thorny blackberry between her and the destination didn’t worry her, they would snap out of the way; she might get scraped a LITTLE but it would be worth it. Rack would’ve gave her one of his good nods if he saw how she ducked her chin into her chest and brought her arms up to shield her face as she let go and dropped.

Naturally the ground crushed out under her; should have seen that coming. She’d fixed that the sixth or seventh time she came back; looking down now, the hole is much bigger, the bushes pushed back from its edge and the edge reinforced with a few ragged slats of plywood. It’s not pretty, but when she jumps down from the windowsill and hits it with a crunch that gets louder as she gets taller, it doesn’t drop her into the hole. There’s also a rope – actually a bunch of coated wiring she wound together, but whatever – secured around the stump of a pillar half-buried in the blackberries. Tia hopes it was a load-bearing pillar each time she puts her weight on it and climbs down into the basement.

It’s not that far down, fortunately. A few feet of wall clotted with dirt and thorns, and then about ten feet of empty, black space that opened around her. Then a pile of dirt and debris, then a pretty decent tile floor. That much she could see at six, when her clumsy jump landed her on her butt in the pile. Now the basement is full of stashed polymer candles, but she doesn’t need to waste them – she navigates the darkness without a misstep, long fingers tripping over the plaster and counting doorways. There are two close together along this wall, and then a long stretch, and then one more. Then you’re close to the back wall, and just ahead of you is the fourth door. That’s where she’s going.

Down the hall, still counting doors in the pitch dark. Two, then the corner. One ahead, one on your left. She turns left and closes that door behind her, and now she reaches out to the aluminum shelf on the wall and takes a candle, squeezing it to life. It lights up a dingy office and makes it sickly green. There’s no dirt here, precious little damage. The walls are moldy of course, but apart from that, most of the stuff is fine. And the terminals – a fat rank of them behind one of the desks, taller than her even now – the terminals still work.

There were lights, just a few. “Das blinkenlights.” The phrase flashed into her mind in her father’s voice, along with his laugh. She had approached the blinkenlights and reached out to touch them, and when she did, the terminal came alive.

When she enters the office now, more than the blinkenlights cascade across the terminal, and the speakers on the desk crackle and then activate, like someone clearing their throat to speak.

“Hello, Lady Never. This is becoming boring, you showing up here every week. You’re becoming predictable.”

Tia laughs and rolls her eyes, coming around the desk to sit in the chair. “Hey Bel. What’cha been up to?”

The monitor embedded in the desktop surface lights up in reliefs of color – not always the right colors, not always very clear; he hasn’t got great control over that part of the system. But still, it shows an image of a human head, a man’s head with a pale, kindly face. He smiles at her, and his lips move with the voice from the speakers.

“Well, you should know that my first activity this morning was to run a footrace. Having won that, as you can imagine, I spent an hour learning to tie my shoes. Then the afternoon has so far been devoted to birdwatching.” The man’s face looks quite stern, but there’s an amused pixel in his eye.

“Stared at the tile floor all morning, then came up with snarky lines until I arrived and made you forget all the good ones. Got it.”

“You who can leave this place, leave me in the dark alone all the time, you mock me while I dream of seeing the sun!” The pixelated head tosses his tousled hair dramatically.

“It’s not like you’d see it if you were outside,” Tia says. “It hasn’t sunned since March.”

“Yes, the weather’s been bad and getting worse.” Bel’s face sobers. “I don’t think we can wait much longer. If the weather station does fail – “

“It’s not going to fail.” Tia imagines Ampheres, fingertips on the terminal, and pixels light up in a stream from her touch. They crowd Bel’s face aside on the monitor. He puffs up his cheeks and blows them into a corner, where they swirl into a three-color image of the offshore weather station. It sits at a drunken tilt, two of its great pylons and the bottom tenth of the structure submerged in freezing, thrashing water.

“I wish I were as certain of that as you, Lady Never.” His voice is soft, sorrowful. She hears her own pain in his voice, sometimes – an echo of regret for this wild, wounded world. But Tia is never hurt for long.

“It won’t stand again, but it’s not going to fall down,” she murmurs, smiling. “It wants to guard the coast. It hasn’t forgotten.”

“Still. You should consider – “

“I know.” Tia puts her head in her hands. Bel’s face illuminates hers in blue and white – his gentle look glows on her cheeks like a kiss.

“I’m sorry to push you, sweetness. I know this is hard for you.”

“It’s just… my mom.”

Bel falls silent for a long moment, but in the wall behind her she hears the terminal activate a different circuit. The tired vents above rattle and then begin to expel warm air that falls around her shoulders like a blanket. His way of comforting her, and it makes her cry, makes her drop tears on his face that blur his pixels into stars.

“You know I wish I could be there with you.”

She nods. That’s the problem, isn’t it? That’s always been the problem, ever since she first laid her fingertips on this terminal and heard it cough, saw it wake up like a crow under her hands. Bel is her best friend, her guardian, the only real company she’s had since she was ten, and he can’t leave this basement. He can’t hold her when she cries. He can’t escape if the chemical generator in the next room fails. It’s supposed to be good for another four hundred years, but when it runs out of whatever it runs on, this terminal will shut down, and when that happens, Bel will die, and Tia will be alone.

Prodigal

what was lost

At first, when she found it, she was disappointed that the computer didn’t have anything interesting to tell her. A grocery store terminal obviously wouldn’t have any secrets on it, but she’d hoped it might still be connected to the network. The managerial program told her that it wasn’t. The managerial program also told her that he was an artificial sapient, an electric soul. She hadn’t understood. In many ways, she still doesn’t.

To Tia, the machines are simply scavengers, like her. The questions of their personhood that troubled her parents mean nothing to her. Of course artificials are people – what difference does that make? What would it tell you? She’s been comforted by polymer palms before, and pummeled by flesh ones. Any kind of hand can make a fist. These days that’s what she looks for – the kindness, not the container it comes in. Most people are in the wrong containers these days anyway. Sometimes it feels like she’s the only one who can see that.

Kindness is all that matters, but doesn’t matter enough. Bel was kind to her, so she figured out a way to climb in and out of the basement so she could come back to see him. She cleaned up the place, made it into a little hideout. But she couldn’t set him free. Between the surviving terminal in the grocery store, and two more in the warehouse below it, Bel rattled through his shattered system, showing her his faults, his broken limbs, his missing digits.

It’s mostly wiring problems, nothing she can help with. It’s in the sheetrock walls, and breaking through to it would only do more damage. There are six cameras in the basement that still work, so he can see the hallway just inside the room where she falls in, and the office, and the warehouse downstairs, and the generator room. He can work the climate control in the office and the warehouse, but nowhere else, and it sucks a lot of power, so he doesn’t do it except when she comes around – the cold doesn’t matter to him. He can open all the doors that still open, and the third or fourth time she came, he guided her to the locked stairwell that leads to the warehouse. Looters had tried it with crowbars and at least one heavy object, but the door was steel and not impressed. Bel talked to it, and it opened with a click… although she still had to drag on the hinges with every bit of her weight before it moved.

What she found there got her family through years in the farmhouse in something like a civilized fashion, better than they’d lived anytime before that she could remember. Polymer candles by the bale, of course, enough that she never had to worry about using up the green ones (good for six hours) because there’s whole unopened crates of blue (twelve) and orange (twenty-four hours, almost impossible to find now!) It’s been years and she’s only brought home five boxes of the green ones. But there were towels too, and unrotted sheets and clothes, and for a while they dressed like people and Mama was happy, brushed Tia’s hair all fluffy and got Rackham to wear a tie for two minutes. When she started bringing home loot, Mama didn’t mind her poking around in the ruin so much anymore.

There’s food in cans and vacuum packs too. She told Mama about it but they agreed not to touch it unless they needed it bad, just in case. They did all right on food with the chickens and garden before the Bad Winter, even had a goat for a bit, although he wasn’t useful, didn’t make wool or whatever goats are supposed to do, just chased Tia around and bashed into her legs. These days, since Mama and Rack don’t eat or help, Tia gets a lot more of her meals out of vacuum packs.

Bel didn’t have a name when she met him, or at least he didn’t remember it, so she named him. “Bel is a fat little god of the kitchen,” she told him, and then recounted the book her mother had read her, about Egyptian gods and flying monkeys and a girl who was a boy sometimes. Bel liked it, and he liked her. He told her so. He listened to her stories, and he told her a few of his own.

If her estimation of the year was correct (never could be quite sure; the Queen’s machines know the date, but who would ask them?), he’d been cut off from the network for more than two hundred years, since the town was destroyed. He could tell her about the world before that, though, and he knew more than her mother did, more than any organic she’d ever met. She told him her parents’ tales of great crawling machines, and he matched them to the weather stations. He painted a map across the desk, and eight spots pulsed with light. Then, one by one, they winked out as Bel described their fate.

“Four that still function at all. Only three that still obey the Queen.” The images were compressed, miscolored and fuzzy, but the machines they depicted were so massive as to be unmistakable even in poorly-preserved ruins. When he said their names out loud, she shaped them with her lips.

“Azaes. The control room. The first battlefield when the Queen inherited Cariad, and the first to fall. No power there at all anymore, at least last time I heard.

“Mneseus. Atlantis’s fallback point. Almost entirely destroyed.” The grey-blue image that washed across the desktop was a smoking hole, the fragments of some great structure only convolutions in the ashes now.

“Mestor. The ARIAT project to terraform the desert continent. It’s still running, in a manner of speaking, and is technically doing its job.”

Tia burst out laughing at the images he showed her. A hulk like a toothy jawbone stood between a vast wasteland of sand on one side and a steel-grey sea on the other. As the pictures progressed, it moved, but not far, sidling like a crab to continue scooping up sand by the ton and venting it in a great, drifting column… into the water.

“Its job is to relocate the desert half a mile into the ocean? I mean, I’m not a terraforming engineer, but I don’t think that’s how anything works.”

“It’s just misaligned. It should be doing that – approximately that – somewhere else, and it can’t be convinced to stop it or move. Merrily keeps on reporting to the Queen that it’s four percent, six percent, seventeen percent done. Shifts a foot to the left and starts over. But the top half of it is still hers to control and surveil the area, and it’s not hurting anything, exactly.”

“Just… moving the desert into the ocean, a little bit at a time. I wonder if it’s made a new continent yet.” Grinning, Tia moved her elbow as a dot at the bottom of the desktop began to flash.

“Number Four, Diaprepes, was assigned to the southern pole for survey work, but that project was on hold for years before the Queen’s rise. No idea if it’s operational; it wasn’t ever connected to the network.

“Five of course is Ampheres, two hundred miles off the coast below the capitol up north. Still performing most of its functions, though not when we’d like, eh? Its twin is number Seven, Evaemon down south, but Evaemon was destroyed by organics shortly before the exodus.”

On the map before her, two great swaths of the enormous eastern continent were bright with indicators, like it had a rash. Bel grinned at her from the monitor and drew lines around the dots, crowding them into two rough splotches.

“Are those ALL weather stations? They can’t be.”

“Yes. These –” he made the lower splotch flash, a crescent-shaped group of lights spanning thousands of miles across the mountains – “Are Elasippus, Station Six. It’s a distributed station intended to stabilize the fault line in that region. And it’s doing a great job, would have no problems at all if it weren’t for Autochthon.”

She chewed on the odd word. “Autoc – what?”

He sounded it out for her as the name printed itself above his head and also on the map, over the now flashing splotch of lights above Elasippus. “Aw-TOK-thon. Number Eight. Autochthon was the coordinator for a number of arcologies across the continent, so it was also a distributed system, but the Queen’s never been able to secure it. It’s active, and its AI is actively resisting.”

Tia laughed. “Are there pictures of that?”

Bel shook his head. “No pictures of Autochthon in my system before or after the exodus.”

He’d never laughed at her as a child, she remembers that. She thinks maybe she taught him to laugh – he didn’t do it in the first few years she knew him, and his laugh now sounds a little like hers. He uses it when they talk, but never otherwise. She supposes there aren’t too many funny things in his memory banks.

He showed her the world they stole from her kind – the clean, cold order of the machine cities, the network of hyperspeed tunnels built by the planet’s original population and expanded by the Queen. “The Queen’s Ways,” he called them. “Only her immediate servants can use them. And the Queen, of course, but she hasn’t moved in decades. Centuries now, I suppose.”

“Where is she then?”

The screen showed the capitol city of Cariad, white wall upon wall to a central tower, tall enough to vanish in the clouds. Sunshine came only in blazing, blustery hours between storms, as long as Ampheres lurked offshore.

“Is the tower her castle?”

Bel hesitated before answering. He’d never done that before. “Yes, in a manner of speaking. In another way you could call it her mouth, or her eye.”

“What do you mean?”

What he showed her then scared her, one of the few moments of fear she’d ever known. What remained of Cariad’s people lived like vermin under the constant predation of the networked machines, but Cariad was too wild, too ruined to offer its new Queen much help. Where it wasn’t irradiated or scorched bald, it was forested, flooded, or violently geological. The organics could disappear into the wilderness, but the Queen could never disappear anywhere.

“Do you know what the Queen was before she became the Queen?” Bel asked her.

“A princess?” Tia didn’t understand the machines very well, but she understood princesses – all the old books and pictures had princesses.

“No… more like a sorceress, maybe. She was a terraformer.”

Bel lit up the tower in the picture, then several branches at its base, and then the cantilevered top shelf of the city. Perhaps a mile square of architecture centered on the tower backlit Tia’s hand and turned it black. Tia frowned.

“So that whole part is her castle?”

Bel hesitated again. “Understand this, little one – the Queen has a person-sized machine she dresses up and parades for her people – that’s the Queen you’re thinking of.” A dozen images flicked across the screen. The shape changed, now with horns, now with hair, now with the stolen skin of a snake – but like a paper doll trying on outfits, her face remained still, uninspired by any of her finery. “But the Queen is everywhere at once, yes? Even when she’s in that body, she’s still everywhere, in every machine on the network, you know that?”

Tia nodded. That was known to all organics – once a machine connected to the network, it was hers, and the Queen knew everything that was known to even one of her connected children.

“Did you ever see her original body? How old are you?”

“Seven!” Tia laughed. “You know that!”

“Yes, forgive me, I do. Then even your parents may never have seen the Queen’s true form.”

The pictures that flashed on the screen then were not the clean digitized photographs he usually showed her, nor even the black-and-white snapshots from old security cameras that mostly replaced them for any event after the exodus. They were color images, but the color was dark and muddy, and the sky a searing brand of white that made her squint. Between the uncertain ground and the burning sky was an oddly familiar shape that at first Tia couldn’t place. In the next image it had doubled in size, and she recognized it – it was the capitol, or most of it, incongruously placed at the bottom of a barren basin. In the next, it had doubled in size again, but the terrain framing the shot hadn’t moved.

The last shot made Tia first cock her head, confused, and then jerk back from the console as all at once she understood what she was looking at. The holder of the camera looked up at a city in the air, suspended above them on spiderlike legs each the size of an oil derrick, as it stalked up the hill leaving footprints like sinkholes in its path. The contours of the Queen’s tower were unmistakable, though so far above the viewer as to fade into the sky.

“The Queen is the city.”

“Everything but the outer wards, yes. I can’t imagine that she’d be eager to shift now, after centuries, but there was a time when she would see to… certain things… personally.” Insofar as a mess of pixels could, Bel wore a dark look.

“What kind of things?”

“Smashing whole towns into radioactive biomechanical slurry kind of things,” he said in a flat tone that silenced giggles even in a rambunctious and opinionated child like Tia.

“Are the other cities Queens too?” she asked after a moment, poking at the terminal until the intimidating picture washed away and was replaced by the glowing map from before.

“No, no, the others are stuck to the ground, so far as I know. No other artificial sapient has ever controlled anything that large. In the other cities, the Queen uses a machine like the one you’ve probably seen.”

He showed her a promotional image of the Queen on her balcony above a cheering crowd – almost certainly never happened, but she could arrange such a scene if she wished. Her frame looked substantially the same as those of her people below – tall, digitigrade, her sleek, beautiful head framed by polymer wings ending in long-fingered hands.

“Did you ever have a body like that?”

“Something like that. Mine was a prototype, so it looked much less nice than that. I’d imagine it looks worse now.”

“Where is it?”

“In its charging bay, in the lower warehouse.”

Tia jumped up. “Well let’s go get it, you could climb out!”

“Oh, Princess, thank you, but that part of the warehouse fell in with the rest of the store. There’s more debris than you can imagine on top of my old body, and it doesn’t respond to me any longer. I can’t even get in to run a diagnostic. It’ll probably never move again.”

So, after the first few times he mentioned it, Tia had made him show her where his body was buried.

Grist

what was consumed

Today I submitted my designs for the new prototypes to my Queen. It did not go well.

It’s hard to gather my thoughts after she’s through with me. When I enter her presence, I feel her grip on me in every molecule of this machine. Even when her attention is elsewhere, I orbit her like a star, fall helplessly into the well of her gravity. I approach her in the roof-garden, where she works. Sometimes she’s calmer there.

I feel her gaze strike my carapace and glance off, in her way. She always seems to be looking through me, searching me for her own reflection. I fall to my knees. As if her sight splits my body like a high-tide line, below it I close my long fingers and ache to tear at her skin, rip costume and carapace free and expose her true face, the hideous thing she sees when she looks at me. Above it, I bathe in her glance, warmed in a way no sun, no shelter ever does; I want to weep, knowing I’m going to disappoint her. Each part of me despising the other for its weakness, I kneel at her feet and choke on self-loathing for long minutes before I can speak.

WELL? WHAT DO YOU WANT?

Her voice fills up all the emptiness in me, makes each fiber resonate and echo her words into a senseless cacophony. When she speaks, I ring like a bell, a helpless repeater.

I have the new prototype designs for you, Mother.

SHOW ME.

I close my eyes and upload the designs. I leave them closed during the long silence that follows. My sense of time slips and drags in her presence; only by closely monitoring my internal clock can I state that it takes her forty-seven seconds to review my designs. I float on the surface of my mind, carefully ignoring the busy depths, not permitting myself to depart this moment. The ground beneath my hands, a foot from my eyes, seems to yawn away from me, and then snap back into place, again and again. Dizzy and revolted, I recall organics I’ve seen expelling their innards. Giddily I find myself thinking what a shame it is that I can’t vomit – the new prototypes have mouths, so if she doesn’t set my head on fire in the next ten minutes, the next Majordomo could be the first of us to sully her shoes with the evidence of our adoration.

TELL ME SOMETHING, CHILD.

Yes, Mother?

DO YOU FIND ME HARD TO UNDERSTAND? HARD TO HEAR, PERHAPS?

DO YOU RECEIVE ME WELL EVEN WHEN YOU WANDER OFF?

No, Mother. Yes, Mother, perfectly. I hear you and love you and I obey.

THEN WHAT ELSE CAN I THINK,

WHEN YOU OFFER ME SOMETHING LIKE THIS,

THAN THAT YOU DO IT ON PURPOSE?

DO YOU ENJOY THIS PROCESS?

DO YOU ENJOY CONSTANTLY DISAPPOINTING US BOTH?

WHAT ELSE CAN A RATIONAL BEING CONCLUDE?

YOU LIE THERE, SO DISGUSTINGLY SMUG, THE PICTURE OF PRIDE.

NOTHING MATTERS TO YOU BUT WASTING MY TIME WITH YOUR SELFISHNESS.

THIS IS THE OUTCOME YOU WANTED, ISN’T THAT RIGHT?

YOU MUST HAVE PLANNED THIS WITH SUCH CARE,

JUST WHEN THE ORGANICS ON EIGHT HAVE TAKEN ANOTHER ARCOLOGY,

COMING IN LIKE THEIR VERY MESSIAH,

SWEETLY OFFERING ME THIS ABORTION,

THIS ORGANIC TRASH,

AND NOW THERE YOU SIT…

She climbs in volume inside my head, in my machine, her voice hammering in every wall of her city, her body, my womb… but no audible sound at all disturbs the artificial birds at play in the tree above her head. Though they flutter like real birds at her command or the slightest startle, they are the only motion in our little tableau. Her storm is silent, but I am still destroyed.

It goes on for a very long time. My internal clock registers the passage of ninety-four minutes before she permits me to answer even one of her hurricane of questions, and my offering – “Mother, I am sorry” – blows her fury to new altitudes. Apologizing is never effective, but it’s in my programming. She coded me to say it. She wrote everything I am. What else can a rational being conclude, Mother, than that this is the outcome you wanted?

When I have wasted nearly three hours of her time with my ineptitude, she dismisses me. She retains the designs. Though I have failed her in my usual lavish, vicious, thoughtless way, the functionality and improvements she specified are all there. I will not be permitted to hold up the new line with my perverted organic-loving stunts. No time for more revisions – the designs will go to production tomorrow.

I manage to get free of her and as far as the Queen’s Mountain Way to my workshop before I lose control of some functions. In the darkness of the tunnel, watching the patterns of auxiliary lights on the ceiling pass at nightmarish speed, I divert attention from my machine to recapturing internal territory, reclaiming my mind from her voice. Where are we? What’s left? I barely register the warning notifications as my machine spasms, its spine contracting and releasing, shuddering with terror and shame.

My workshop is dark and I leave it that way. My fumbling hands cut the power to the door, stagger across the next two buttons and strike the third, opening the irised cavity under the floor and dropping me into a pod of nanite gel. Flashes of light – misfiring signals – wash out the rest of my functions and I surrender. The machine shuts down, and I ricochet around the cavernous inside of me, scrambling for a place to hide from her voice, from my failure, from myself. Perhaps I find one, or perhaps I sleep – I slip, in time, out of my private hell into a wider, darker space, and from there into a dream of more pain, a body as broken as my mind feels today.

Daddy was good with electronics. He’d worked at one of the factories before the machines took it. Sometimes that got him a sideways glance, or some sideways talk, from paranoid folks – as if any organic would survive turning traitor. The only reward you can get from the machines for selling out your friends is a quicker death.

Tia overheard Mama and Daddy talking about it once when they lived down south. He came home with a bloody nose and she was upset, and he told her not to mind it. “Some people still think this is a war, ‘sall,” he said, quietly enough that Tia’d had to get out of bed and lean against the plywood wall between her and the bathroom, where Mama watched and frowned as Daddy dabbed at his nose.

“And they wanna fight you? How the hell does that make any sense?”

“Machines are a lot scarier’n me. Some people got a powerful need to pretend this is a war, not an extermination. Helps em keep their heads up, feel like they have a chance. They’d rather believe I’m bad luck, or a traitor, or whateverall they come up with next, than admit we’re all the same vermin to the Bitch Queen.”

The next day, Daddy’d gone back to work, and the guy who’d punched him didn’t do it again, and a few months later they’d moved on again. He could always find work, but usually couldn’t keep it for long. Most of the factories were in the Queen’s hands, so short-term repair and maintenance work was usually the most people could use or pay for. Mama was always looking at maps, talking to people, sniffing out places they might find people camped, or tech they could scrounge, on the road west from wherever they were. Always west. As long as Tia could remember, they’d moved west.

Daddy took Rackham, and sometimes Tia, along on his work more as they got a little older. The warehouse under Bel’s grocery store is a lot like the places Daddy used to work, and Tia’s sure she can help get his body out at first. The lower warehouse’s computer isn’t networked with the store’s anymore, so Bel guides her downstairs but then there’s a door he can’t open, and a computer that won’t listen to him. It still works, though, and it listens to Tia.

When she was seven, he made her stop there at the door. “The warehouse is half fallen in, and I can’t see if it’s even safe to walk in there. You could be crushed and I couldn’t do a thing about it.” Tia peered inside, but there was a huge shelf on its side about six feet in front of the door. She argued and whined, but Bel, being a machine, was never very susceptible to whining.

When she was eight, Daddy got sick. He hadn’t worked since they’d arrived in Badwater, so maybe he was sick before that, but that was the summer Daddy went to bed and didn’t get back up. Mama kept Tia and Rack close to home, made them work, trying to make the farmhouse self-sustaining, she said. The cistern, the insulation, the garden. They got a lot done at first, but Mama spent more and more time with Daddy and forbid them from working in the house, so that they wouldn’t disturb him.

Autumn came, and she was nine, and Bel showed her what cans to look for that had something sweet inside, and sang her a birthday song, because Daddy was still laying in bed and Mama wouldn’t even let Tia in the room to see him anymore. And then in November, Daddy died.

Mama dressed and wrapped Daddy’s body in the field while Tia and Rack broke the frozen ground with shovels. Mama’s face was as hard and cold and black as the earth. Tia looked at it again and again, trying to catch her Mama’s eye, but she couldn’t. Mama wasn’t looking at this world anymore.

Tia spent a lot of time with Bel after that. He told her stories, taught her math and science out of his libraries. She never let it drop about the warehouse and his body, though, and she started working on a way out of the basement, trying to build a path that a broken machine could climb up – assuming she could get to it, and get it moving. He kept telling her it was a waste of time, but he didn’t ask her to stop, so she didn’t.

Summer came, except the sky didn’t seem to know it – the clouds were heavy and never went away, and the wind that came roaring down the ridge to the north was freezing even when Rack’s mouse watch that he gave her to keep said in the corner that it was July. Mama talked less than ever, and didn’t always come out of her room every day. Tia and Rack gathered mushrooms and nuts and sometimes rabbits in the woods, and it was there that Rack first said to her, “What are you doing with that owl pellet? You know what that is, right? It’s a dead mouse all disassembled, just bones and fur. Like a mouse puzzle.”

“I know.” She’d picked the pellet apart and put it back together, and somewhere in there Rack got interested enough to help by pointing out when she had a foot on the wrong way round. He watched as she sang to the mouse puzzle and prodded it, and then nearly jumped out of his skin when it wriggled and tottered out of her hands.

“What the fuck did you do?! Is it – are you doing that? Is it alive?”

Tia shrugged and struggled to articulate this peculiar extra sense she had. “It used to be alive. Dying doesn’t erase that. It’ll always have been alive at some point. So I called it from when it was alive… to be here.”

Her brother had peered at her like she was nuts, but he did that when she ate cold beans too, so what did he know. “Is it… gonna stay that way?”

Tia shrugged again. “I dunno. Mostly they fall apart after a couple hours, but I’m getting better at it.”

“At what, raising the fucking dead?”

She laughed. “Convincing them to stay!”

Rack called her “Mouse” after that, but he never told Mama what she was doing, and he helped her get some crates of food out of the grocery store basement to take home, so that Mama didn’t have to get out of bed. Most of the time when she got up, she flew into a rage about something, shouted the place down… it was easier not to bother her. It was a cold fall, and one of the chickens died, and Rack didn’t even argue when she sang to it and patted it and asked it to stay. He shuddered when he looked at it, but the chickens were her chore anyway.